- content words: lexical items, 's, VB's, adjectives.

- Function words: prepositions, pronouns, quantifiers, demonstratives.

- they indicate relationships between words (lexical items)

- have as their source, originally, lexical items: e.g. modern

E. "while" comes from "þa hwile þe" (the time that).. (Like

Tamil

pootu "time" --> -ppa as in poorappa 'when s.o.

goes".

- Types (or classifications) of Grammaticalized'd forms:

- Not all grammaticalized'd forms are independent words: they may be

bound forms or perhaps they must be bound forms (i.e.

are or must be attached to some other morpheme.)

- Or, there may be a continuum, with clusters or focal points:

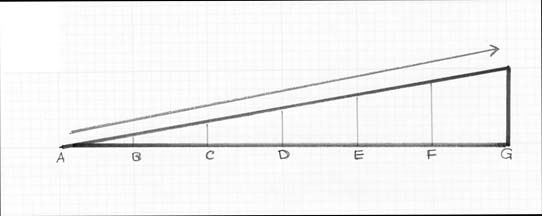

Lexical >-------A--------B---------C---------> Grammatical

That is, the "path" from lexical item to grammatical item is not a smooth, interrupted one, but there may be "stages" along the way, with "rest-stops" or intermediate points in the Grammaticalization process. It's slow, and steady, but with pauses. At those pause points, we may discern certain features.

If we see Grammaticalization as the end point, then its features are:

- Grammatical words with relative phonological and syntactic

independence: e.g. English prepositions at the end of a sentence; have

full segmental structure: [aet], [In], not [@t, 'n] and can be stressed:

"Where's he at ?

- Derivational forms: content words may have affixes that are not

inflectional nor clitic but don't affect the category (don't

cause change of gram. cat.): duck + ling (both nominal).

- Others change category: Noun: swimmer (< vb. swim + er). These

affixes are somewhere between content and function; derived forms can then

be inflected and/or cliticized: swimmers

- Clitics: not affixes, but can only occur next to autonomous word.

an autonomous word becomes a clitic by cliticization :

- 's me (it's me)

- I'm (I am)

clitic pronouns, clitic discourse markers (Tamil -ee, -oo etc.) are examples.

- Inflections: always dependent, bound, part of another word.

- Grammatical words with relative phonological and syntactic

independence: e.g. English prepositions at the end of a sentence; have

full segmental structure: [aet], [In], not [@t, 'n] and can be stressed:

"Where's he at ?

- back (lexical item, the back of the body) --> in back of (behind) --> (go) back.

- Noun ---> relational phrase --> adverb --> preposition.

- Tamil: pin --> pinnaale , or pakkam+le --> pakkattule; or -il+irundu --> lerundu ('ablative').

- These things change from locational (spatial) to temporal.

There is disagreement as to where, how many points there are on the cline. Some argue that the path should be: context item (lexical item)--> grammatical word --> clitic --> inflectional suffix.

as in X full of Y --> X-ful --> hopeful.

Hopper & Traugott are much concerned with the cline of grammaticality, and its conceptualization. Some (Heine) are concerned with how one thing seems to imply another; whether there are channels that are followed (paths), or push-pull chains (?), or inferencing.

H&T say that at least we must recognize:

- There is an order, with points ,

- the order is unidirectional

- there may be channels (Heine) or paths along which forms travel

- certain things happen at the cluster points (e.g. "bleeding" of meaning)

- There may be chains with internal structure and/or relational patterns (X implies Y; A leads to B; C determines D),

This needs to be worked out (below).

- Not all grammaticalized'd forms are independent words: they may be

bound forms or perhaps they must be bound forms (i.e.

are or must be attached to some other morpheme.)

- One more point: note the dichotomy between the periphrastic and the

bounded:

/\ / \ / \ / \ / \ / \ Periphrastic Bounded have waited waited TENSE of the X X's POSSESSION more curious curioser COMPARISONWhat starts out as periphrastic becomes "synthetic", i.e. is realized by affixation; the diachronic tendency seems to be toward affixation. Periphrastic constructions (they say) coalesce over time and become morphological. Other examples:

- Definite articles becoming affixes in Scandinavian, in Istro-Romanian, e.g. Danish

-en and -et ( dreng-en 'boy' and hus-et 'the house' are definite articles that were previously postposed in Old Norse. Also passive as in Scandinavian. - Use of aux. verbs to form tenses periphrastically, such as Hindi pres.

tense, Romance languages use of formerly periphrastic tenses e.g. cantare habemus

(Latin. we have to sing) --> Ital. canteremo 'we will sing.' (

cantarabemus --> cantaremos .. ).

- Maybe Tamil -aam modal is an example of this kind of development from aakum i.e. pookal + aakum 'going will happen' --> pookalaam 's.o. may go.'

- Second diachronic tendency that makes periphrasis/bondedness distinction important is renewal i.e. tendency for periphrastic forms to replace morphological ones over time, in a kind of cycle, which they illustrate with examples from I-E, Latin, and French on pg. 9. The peripheral. form becomes reduced and morphologized, then it is replaced by another peripheral. form, which is then morphologized, and which is then it is replaced by another peripheral form, etc. Each new form has some nuance of meaning diff. from the previous, but eventually it takes over, coalesces/reduces, and then is replaced. (Cite Hodge 1970 for many examples of this; see D.N.S. Bhat on evolution of tense forms in S. Dravidian, which show incorporation of forms of iru as past tense markers, which then get reduced and require renewal.)

- More examples .

- Let's (let us) --> lets (let it be the case that; let it happen that)

with a meaning of 'adhortative' or 'first person imperative' or even 'condescending

encouragement' of 2nd person ("lets eat our liver now, Betty").

This shows various stages:

- full verb let has altered its semantic range somehow.

Perhaps

Grammaticalization in early stages often/always shows shift in meaning , and only

in a spec. context, here the imperative. Permission or allowing has

become extended (in part of the paradigm) to encouraging or

suggesting s.o. to do s.t. Let has become less specific, but

also more speaker-centered or centered in speaker's attitude

to the situation . (Began in 16th century or earlier.)

- First-person plural. pronoun us became cliticized ( let's

and from word-plus-clitic we get single word lets . This is fine

as long as still used with plural subjects, but when used with singular. subjects,

we can't do this any more. Final s of lets loses its status as

separate morpheme. This illustrates a general shift of

word --> affix --> phoneme -

Next stage brings more phonological reduction i.e. [ts] is often reduced in rapid speech to [s] as in le's go or even 'sgo ; come on, let's go --> c'mon, sgo [kmã:sgo]

-

Next we have the routinization or fixation of a meaning

or discourse function for lets that was formerly freer; it's on

its way to Grammaticalization , singling out something from a whole paradigm of forms and

specializing it as (here) the adhortative :

This form does not have the meaning Permit him to go... but rather "I suggest he go ..." H&T say this is provisional and relative, not permanent; it may not survive, but for now it is available and helps to build interactive discourse (this is what they mean by these things being more attitudinal, speaker-centered, discourse-centered and interactive.Let'm go to hell, I don't care.

- full verb let has altered its semantic range somehow.

Perhaps

Grammaticalization in early stages often/always shows shift in meaning , and only

in a spec. context, here the imperative. Permission or allowing has

become extended (in part of the paradigm) to encouraging or

suggesting s.o. to do s.t. Let has become less specific, but

also more speaker-centered or centered in speaker's attitude

to the situation . (Began in 16th century or earlier.)

- H&T's next example is of a process in Ewe very similar to Tamil!

There is a verb [bè] which means 'say' which is being grammaticalized into

a complementizer whenever a verb other than [bè] is used

in the sentence: this is obviously similar to use of Tamil en- as

a complementizer ( enru ) such as 'He said that he would come' i.e.

For more discussion of this in Tamil, look here . As they note, the verbs involved are verbs of speaking, cognition and perception; they are similar to a verb meaning 'say' because they can have objects that are propositions. Same in Tamil/Dravidian, where the verbs that can use enru as the complementizer or embedding marker are verbs like nene, nambu, utteesamaa iru etc. ('think, hope, have the intention, etc.') But, the meaning and the morphology of the 'say' verb (in both Ewe and Tamil!) is essentially lost in the Grammaticalization of it as complementizer. In Tamil, of course, it also is phonologically reduced by loss of the initial vowel e . Syntactically, as they illustrate on pg. 16, there is also shift from [x[y]] to [x[y[z]]]. In Tamil, it would be change from :avan naan vareen-NNu sonnaan [[avan naan vareen]-NNu sonnaan] . to[[[avan naan vareen]-NNu] sonnaan] . - Agreement Markers. Here H&T give an example of an already grammaticalized form becoming more grammatical. They give example from French where il which is the masc. pronoun has become (in non-standard Fr.) AGR and is bound to the verb, not signaling gender:

ma femme il est venu

my wife AGR has come(This example not very satisfying to me.) How about the example of Tamil accusative marking becoming the marker of definite-ness? as in:

naan pustakam paDicceen 'I read a book' naan pustakatte paDicceen 'I read the book.' - Agreement Markers. Here H&T give an example of an already grammaticalized form becoming more grammatical. They give example from French where il which is the masc. pronoun has become (in non-standard Fr.) AGR and is bound to the verb, not signaling gender:

- Definite articles becoming affixes in Scandinavian, in Istro-Romanian, e.g. Danish

Summing up: Grammaticalization raises many questions, many of which are as pertinent for Tamil as they are for EWE or for other languages. I wonder whether we focus too much in descriptions on standard languages and ignore the colloquial, where we find (e.g. in English) interesting things that tend to be ignored; in Tamil we don't have this luxury if we are to adequately describe the language most people speak but don't treat seriously. Perhaps grammar is a way-station, constantly being reorganized, and Grammaticalization is a voyage that makes stops from time to time.